Cookies

Cookies present issues for website owners and users alike, and they’re nothing new. While the GDPR and PECR legislation have encouraged companies to proactively consider user privacy, the basic cookie requirements are neglected on a large number of sites.

Cookies fall into two categories: essential and non-essential. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) describes essential cookies as:

…strictly necessary to provide an ‘information society service’ (eg a service over the internet) requested by the subscriber or user. Note that it must be essential to fulfil their request – cookies that are helpful or convenient but not essential, or that are only essential for your own purposes, will still require consent.

Good examples of this would be cookies that determine whether a user is logged in or not, remembering the items in a user’s shopping basket, etc.

Everything else is a non-essential cookie.

That might include cookies that:

- Improve a user’s experience

- Provide marketing data (e.g. Facebook Pixels)

- Track users around the internet

The same cookie might be classified differently on two sites depending on the functionality that a site requires.

Prior consent

One of the key points around cookies in the PECR is that websites must seek consent before setting non-essential cookies:

Just because users may be unlikely to select a particular non-essential cookie when given the choice, or because the cookie is not privacy intrusive, is not a valid reason to pre-enable it.

Crucially, analytics cookies are not classed as essential, therefore permission should be sought before these are set.

The ICO article goes on to further explain – in clear terms – what is considered valid consent. Valid consent does not include cookie banners that:

- State “by continuing to use this site you accept our use of cookies”

- Over-emphasise “Agree” or “Accept all” buttons

- Don’t allow users to make a choice

I don’t have data on this, but almost every website I’ve checked that uses a service like Google Analytics sets the cookie before the user accepts/rejects permissions. Many of these don’t give users the choice to turn non-essential cookies off.

These breaches aren’t limited to small companies that may not have the resources or time to fully explore/understand these laws.

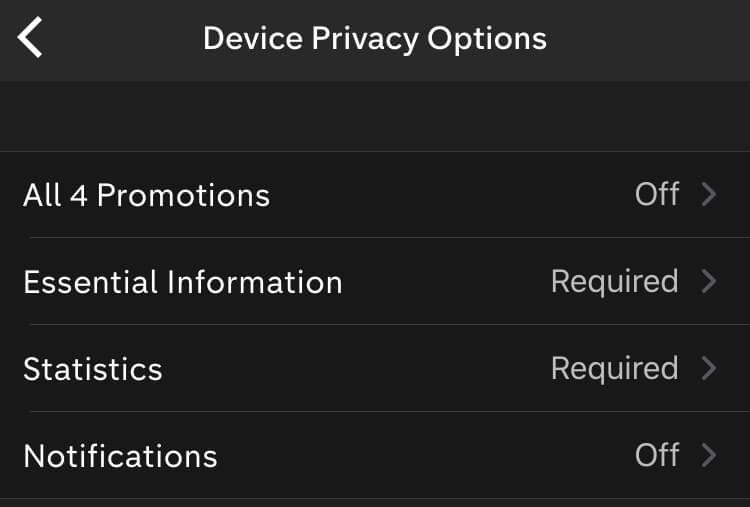

Here’s a screenshot of the cookie permissions page from Channel 4’s All 4 app:

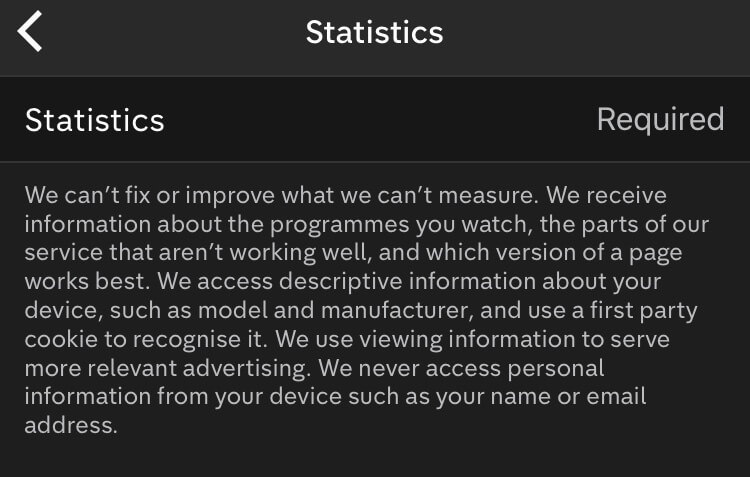

It’s impossible for users to turn off analytics cookies. Channel 4 explains their rationale for requiring this as follows:

In short, they justify the use of requiring these cookies on the grounds that:

- They want to ‘improve’ the service

- They need to know what device you’re using

- They want to serve more ‘relevant’ ads to you

Apparently, that’s all ok because they ‘never access personal information from your device such as your name or email address’.

That seems reasonable, right? Yes, except for two points:

- Using the app requires a user to be logged in. That means the information is already associated with the user (irrespective of accessing a name and email address).

- Setting these cookies is explicitly prohibited.

This is an organisation that clearly have the resources to be clued up on this stuff. And they’re not the only ones to ignore these regulations: I’ve seen many companies take a similar approach.

Why don’t they comply?

The underlying issue is that if sites fully complied with these laws, their current methods of collecting analytics data would mean their data is seriously inaccurate. Every user who didn’t specifically allow statistics cookies would not be counted and their movements around a site wouldn’t be tracked.

There are privacy-focused alternatives, like Fathom (that’s an affiliate link) or Simple Analytics, but the technical limitations of not setting a cookie limits the available data. To truly comply with the regulations would require companies to take a different approach to collecting and interpreting the available statistics.

That may also mean a change to online advertising models, too.

These are not bad things.

But while companies feel free to flout the regulations, analytics data is cheap and easy to come by: “cheap” if you’re not the user, that is.

Future solutions

Banners and notification overload are one of the difficult things about this whole malarkey. Even if a website uses a cookie wall, many users will accept all cookies because:

- They just want to get rid of the banner

- It might be the highlighted option

- The microcopy might be confusing (e.g. “Accept all”, “Accept”, “Save” or “Save all”)

Or they may even be happy to have their data collected.

We already know that users don’t like waiting a long time for a website to load. The last thing they want is to wade through a load of complicated – and technical – options to decide on cookie use.

One solution would be for this to be tackled at the browser level. Browsers could define a way for websites to declare essential and non-essential cookies: the latter could be further divided into common subcategories (“Marketing”, “Analytics”, etc).

Website owners could then hook their cookies into these and users could set their default preferences for all sites, with exceptions as they want.

A widespread approach like this would encourage companies to finally take note of the cookie requirements, but it’s difficult to see this happening.

Google develop Chromium which powers Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Brave and others – possibly as much as ~60% of internet browsers. They almost certainly benefit from the data collected through Google Analytics and Google Ads – both services that need cookies to work best.

For general internet users concerned about online privacy and whether companies should be rewarded for ignoring regulation, now would be a great time to consider using Firefox as their main browser. It’s an excellent browser with a privacy-focus, demonstrated by their recent rollout of Facebook containers that stop Facebook tracking users around the web.

Browser diversity is important for all users if the web isn’t going to become a monopoly. If there is only one browser – and that browser happens to be controlled by a company who benefit greatly from the collection of ‘free’ data - the future for user privacy looks bleak.

Posted in:

- Journal

- Opinion